In 1964, Clarence Brandenburg, a KKK leader from Ohio, invited local media reporters to cover a rally where a handful of his supporters were in the audience. While Brandenburg himself was unarmed, several of his supporters in the audience were, and during the course of his speech, he stated that “we’re not a revengent organization, but if our President, our Congress, our Supreme Court, continues to suppress the white, Caucasian race, it’s possible that there might have to be some revengeance taken.”

While there is no denying that Brandenburg’s speech consisted of incredibly vulgar language, the Supreme Court looked closely at the threat of “revengeance” that he alluded to. In the aftermath of his speech, he was arrested for violating an Ohio law that criminalized the advocacy of the “duty, necessity or propriety of crime sabotage, violence, or unlawful methods of terrorism as a means of accomplishing industrial or political reform.”

The justices of the Supreme Court reversed this conviction, writing that:

The constitutional guarantees of free speech of free press do not permit a State to forbid or proscribe advocacy of the use of force or of law violation except where such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action.

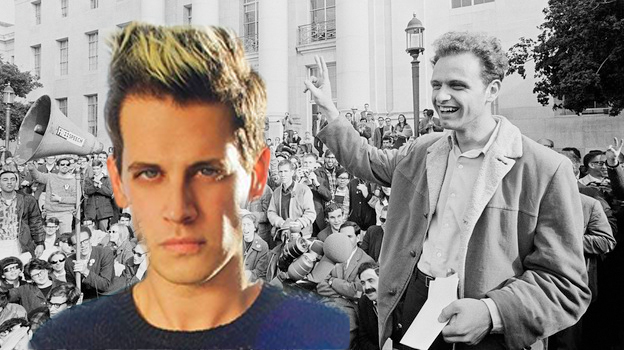

The parallels between Brandenburg and Milo Yiannopoulos’ recent attempt to speak at UC Berkeley are obvious. Milo’s detractors argue there is hardly a dime’s worth of difference between what he has to say and what Brandenburg spoke about decades ago. However strongly people may disagree with Milo’s speeches, he does not threaten “revengeance,” now or down the road.

If only non-controversial speech were covered by the First Amendment, there would barely be a need for it to begin with, because people would have no objections to it.

Additionally, if only non-controversial speech were covered by the First Amendment, there would barely be a need for it to begin with, because people would have no objections to it. The First Amendment needs to cover topics that raise objections. 90 years ago, Justice Louis Brandeis stated that “fear of serious injury cannot alone Justify suppression of free speech and assembly…the remedy to be applied is more speech, not enforced silence.”

The only thing preventing people from engaging in dialogue and discussion with Milo to challenge him on his ideas was the riot itself. The violence that erupted was shocking but far from unexpected, with the Berkeley Police Department receiving a letter that read, in part, “you can protect Milo but you will not be able to protect [College Republicans President] Jose Diaz.”

To its credit, Berkeley itself refused to cancel Milo’s appearance until the protests made it incredibly difficult for it to proceed (although it did charge College Republicans a security fee of several thousand dollars, which was waived after the speech failed to take place). Its chancellor’s office stated that “our Constitution does not permit the university to engage in prior restraint of a speaker out of fear that he might engage in even hateful verbal attacks.”

“Not a Proud Night” for Berkeley

Prohibition against prior restraint of speakers has been a critical element of First Amendment doctrine in America for centuries. A university spokesman said that the night of riots was “not a proud night for this campus, the home of the free speech movement.” The protesters who shut down this event did so in direct violation of Berkeley’s wishes

This entire incident demonstrates how universities can either abide by their histories of supporting free speech or abandon them to the loudest voices at any given moment. As a student at the University of Chicago, I have been lucky to attend an institution that considers itself a leader in the free speech movement. Our history with free expression dates back at least to the 1930s, when a Communist Party leader spoke on campus. At the time, UChicago President Robert Maynard Hutchins defended the hosting of Foster, saying “our students … should have freedom to discuss any problem that presents itself.”

“free inquiry is indispensable to the good life, that universities exist for the sake of such inquiry, [and] that without it they cease to be universities.” – UChicago President Robert Maynard Hutchins

Hutchins later summed up the importance of open inquiry in higher education: “free inquiry is indispensable to the good life, that universities exist for the sake of such inquiry, [and] that without it they cease to be universities.” If only more presidents of universities had the conviction to echo that statement these days.

Fortunately, UChicago has continued to build on its legacy with Professor Geoffrey Stone’s Report of the Committee on Freedom of Expression and Dean Jay Ellison’s famed letter to UChicago’s Class of 2020. With any luck, more schools will look to us as an example for the Classes of 2021 and beyond.

How does the Brandenburg standard apply to cases like this? The three key elements of this standard are held by many First Amendment experts to be: intent, imminence, and likelihood. However, the standard can’t quite be applied to Milo’s scenario, because the riots happened before he started to speak. That said, it is all but guaranteed that Milo’s speech would have been protected and that there would be no First Amendment justification to restrict his talk under the Brandenburg specifications.

A Supreme Court precedent that is also pertinent to this instance is that of Terminiello v Chicago, where Arthur Terminiello gave a speech that was critical of various racial groups, and where he also egged on the protesters, whom he referred to as snakes, slimy scum, and more. The protesters who were gathered outside smashed the building’s windows and threw stink bombs into the crowd packed inside. This doesn’t nearly approach the damage caused to Berkeley’s campus, which might run into the hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Despite how Terminiello was arguably “asking for” the protesters to disrupt his event and destroy property, the Supreme Court held that “a function of free speech under our system of government is to invite dispute….or even stir people to anger. [That] is why freedom of speech, though not absolute, [is] nevertheless protected against censorship and punishment, unless shown likely to produce a clear and present danger of a serious substantive evil that rises far above public inconvenience, annoyance, or unrest.” The definition of “substantive evil” is relatively subjective, but it is important to remember that Milo’s words did not produce the riots at Berkeley: protesters were rioting over the fact that he was going to speak later that day.

Berkeley was once home to a vibrant free speech community, but their work seems to be forgotten by the protesters of today.

Milo Yiannopoulos’ visit to UC Berkeley clearly demonstrates how much work needs to be done on college campuses. Berkeley was once home to a vibrant free speech community, but their work seems to be forgotten by the protesters of today. Unfortunately for them, the law is not on their side.